NJ could see 800 babies in withdrawal from drugs in 2018

In September alone, five babies were sent to Children's Specialized Hospital in New Brunswick to help them withdraw from the drugs they became so used to inside their mother's womb.

The hospital's Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome Program, established several years ago, has seen a steady increase in activity year after year, mirroring trends on the state and national level.

"This year we are on track to have approximately 800 babies delivered in the state with Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome," said Colin O'Reilly, chief of inpatient services for Children's Specialized Hospital.

According to new data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, opioid use disorder among pregnant women, around the time of labor, quadrupled from 1999 to 2014. From 2008 to 2016, cases of NAS doubled to 685 in New Jersey, according to the New Jersey Department of Health.

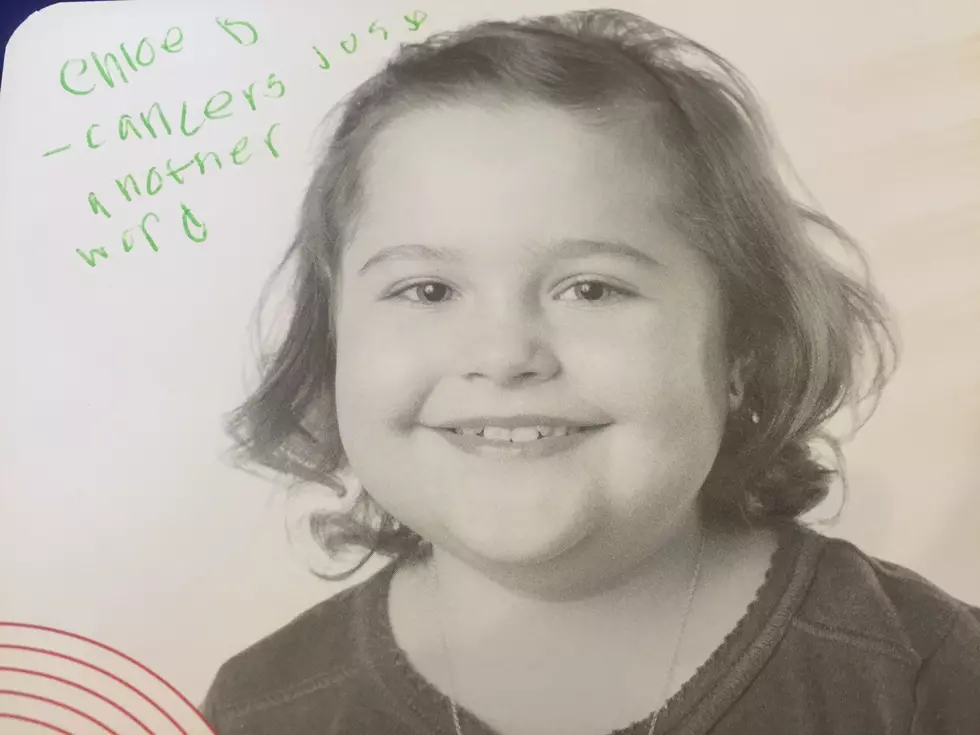

The department in April launched an awareness campaign to take on the problem. It not only highlights the potential impact of addiction on babies, but educates women of child-bearing age that medication-assisted treatment is beneficial to both the mother and unborn child.

At nearly 60 percent, heroin is the most commonly used substance among pregnant women, according to 2015 data from the New Jersey Substance Abuse Monitoring System. Other opiates represent 9.7 percent of the problem.

But instances of NAS are not always the product of women doing something wrong, O'Reilly said.

"Oftentimes pregnancies occur when people are taking prescribed medication," he said.

Babies typically start experiencing withdrawal symptoms two to three days after birth. They can experience issues with breathing, feeding, digesting and sleeping, and may be excessively irritable.

A structured program, O'Reilly said, ensures babies avoid acute withdrawal.

"Every four to eight hours, we're scoring the child for symptoms of withdrawal, and we're adjusting our medication regimen based on that," O'Reilly said.

The multidisciplinary approach also addresses the parents, making sure they understand the individualized care necessary for their child in order to help them reach their full potential.

Later in life, these children are at greater risk of learning disabilities, developmental delays and attention deficit disorders, O'Reilly said. Patient care coordinators work out ongoing support for families after the child is discharged from the program.

More From 94.3 The Point